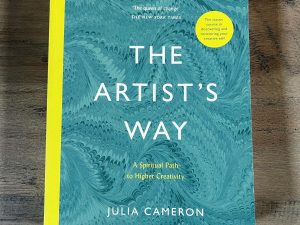

As we inch toward the end of The Artist’s Way, some loose ends begin to wrap up. Week 9 closes out the prior weeks’ thoughts on our negative conditioning, revealing what keeps us blocked. It also provides us with insights into what we need to do to start and sustain our creative work.

Fear: What’s in a Name?

Blocked artists are not lazy. They’re blocked.

Week 9’s theme is one of compassion, the kind that artists likely need when recovering from the losses discussed in week 8. Cameron introduces this theme by investigating how we label ourselves. She observes that artists often engage in negative self-talk by calling ourselves lazy when we fail to get creative projects underway (never mind finished). Gently disputing this opinion, she states that we actually are blocked. To prove her point, she recounts how much energy we spend on feeling of self-doubt, regret, and grief (among others). Our artistic inaction, she asserts, is caused by being blocked, and as she reveals, we’re blocked due to fear.

Cameron doesn’t specifically draw out why our calling ourselves lazy is so harmful, but we can readily observe how blaming our “lack” of willpower turns to shame when we fail to get artistic projects underway, in turn begetting a cycle of regret because that fear remains unnamed and unaddressed. For Cameron, calling things by their right name is not a matter of semantics[*] but an act of compassion, because we cease scolding ourselves when we acknowledge what truly impedes our artistic endeavors. Moving deeper into this conversation, she explores what makes us afraid, focusing on how these fears (eg, fear of abandonment caused by parental displeasure[†]) may contribute to an artist’s desire to be wildly successful.

The internal pressures fueling our ambitions and need for success (regardless of the source), however, make it challenging to either create art or be an artist. As Cameron reassures us, we should regard any difficulties in getting going as an indicator that we need help versus a sign that we’re not meant to be artists. Such help comes from our supporters, higher powers (if one is so inclined), and ourselves (eg, “filling the form” from week 8). Conquering our fears, according to Cameron, requires us to love our artist. Normally verbose on these matters, her instruction here doesn’t exactly explain how she envisions this working—which would’ve been helpful—but surely the impetus to be kinder to ourselves is an excellent place to begin.

Enthusiasm as Motivation

Remember, art is a process. The process is supposed to be fun.

In the next section, Cameron answers an unposed question: How do we keep going once we’ve finally got those artistic projects started? Many of us believe that rigid discipline, powered by an artist’s indomitable willpower, is the answer. Cameron’s disdain for self-will, long a familiar sight to readers of The Artist’s Way, surfaces as she somewhat uncharitably states that this belief merely panders to one’s ego (making discipline our source of pride opposed to creativity). Discipline, she argues, only delivers temporary results. What sustains us as artists is enthusiasm.

Throughout The Artist’s Way, Cameron firmly states that art is meant to be an enjoyable process. Enthusiasm, in her view, is both a “spiritual commitment” to this process that allows us to recognize the creativity surrounding us and a source of creative energy flowing from “life itself”. Therefore, it’s the joy that we experience from our artistry that keep our artistic momentum going more than our slogging through a schedule. While we may still set schedules, we use them to plan our creative playdates. Similarly, our works areas are more likely to be a bit messier and colorful than the “monastic cells” that we tend to associate with disciplined artists. After all, our artist child self is more likely to create art when their efforts feel like play and their workspaces resemble playgrounds.

The one question Cameron hasn’t answered, however, is how enthusiasm relates to compassion. Between the lines, though, one might note the exclusionary whiff associated with discipline as would-be artists see this as the obstacle to their becoming artists. Subscribing to the myth of discipline is another way in which we’re unkind to ourselves, as this belief implies that creating art requires great willpower that only certain people possess. In truth, creativity is available to all, once we give ourselves permission to have fun and see what happens.

Creative U-Turns

A successful creative career is always built on creative failures. The trick is to survive them.

Week 9 opens with Cameron urging us to keep going, noting that we’re on the cusp of learning to disassemble our emotional blocks. It’s an appropriate warning, as impending success is when we most often experience a creative U-turn. As mentioned previously, creative U-turns are losses associated with self-sabotage (eg, opportunities we refuse). Cameron, as promised in week 8, returns to creative U-turns to flesh out why they occur and how to deal with them.

Cameron cautions that some artists might feel threatened by their approaching recovery and balk at this progress. Others may find it easier to remain “victim to artist’s block” than to take on the risks of being a productive artist. While Cameron is wearing her “tough love” hat here as she uncomfortably points out how we resist recovery, she also wants us to be sympathetic when we reflect on our U-turns, because creativity has its frightening moments. We can, as she suggests, look at such moments as “recycling times”, that is, moments when need a few tries before we succeed in making a creative leap. However, she emphasizes that creative U-turns happen in all artistic careers—a point so important she mention it twice in short succession before providing a lengthy list of artists who themselves had creative failures preceding their eventual successes.

Failure is a part of the creative process, but it is survivable. To do so, we need to recognize that our creative U-turns or series of U-turns represent a reaction to our fear.[‡] Once we’ve acknowledged our U-turns and their sources, we need to seek help. To begin, we can outline what part of the creative process makes us feel uneasy. We might give ourselves confidence by building up to these difficulties (eg, trying a workshop before seeking an agent). We also can tap into our resources by asking other artists we know for assistance. As Cameron assures us, the help will come.

Blasting Through Blocks

Blocks are seldom mysterious.

Perhaps the most exciting part of week 9 involves some advice on how to “blast” past our artist’s blocks. Cameron maintains that we need to be relatively “free of resentment (anger) and resistance (fear)” before we can work on our artistic projects. Therefore, we first need to consider what undisclosed concerns exist with a project or whether we have some lingering, unstated payoffs for not working. As she observes, our blocks are relatively straightforward: they act “artistic defenses” against what we may feel is an unsafe situation. Our mission, therefore, is to assure our artist child that it is safe to proceed. Cameron closes this week by providing a short questionnaire that’s aimed at unearthing these concealed barriers to artistic work, which she indicates is also helpful for clearing away obstructed flow in instances where the work becomes challenging (for an abridged version, see the text box).

Some Closing Thoughts

Week 9 ventures into both new and familiar territory as it persuades us to treat ourselves compassionately. While Cameron’s not one to shy from tough talk should she feel it’s necessary, this push to be kinder to ourselves is as valuable as deepening our understanding of how we artistically block ourselves. We’ve all experienced failures in our artistic lives. But we rarely do we let ourselves off the hook for them. There’s something comforting in being permitted to recognize our fears, let go of shame, and accept that we can move past our creative U-turns.

What particularly resonated with me this week, however, was Cameron’s insightful conversation on calling things by their right names. Being told I wasn’t lazy lifted a weight I hadn’t known I was carrying until I realized that my undone projects had little to with my drive.[§] This section makes the case as to why willpower and ego aren’t to blame for our artistic works in limbo—or sufficient in themselves to get us across either the start or finish line. In doing so, Cameron also highlighted (perhaps inadvertently) how dangerous negative self-talk is. Here, it works as a subtle pattern of self-shaming that convinces us we haven’t what it takes to be an artist while neatly preventing us from dealing with the fear blocking our path. This behavior does a tremendous disservice to our creative lives and likely elsewhere. It’s something that gave me pause even as I enjoyed the sense of liberation I felt at being judged “not lazy”.

Many chapters in this book deal with difficult subjects (shame, anger, jealousy, etc), with week 8 focusing heavily on our artistic losses. It’s easy to see why week 9 might seem like a good place to call it quits. Despite the time it took for me to get to and through this week,[**] I found it to be among the more positive experiences with this book thus far, because Cameron’s advice here generally is useful and easy to enact. While I continue to long for Cameron’s writing to stay a bit closer to the point or to explain how love will conquer my fears, week 9 overwhelmingly is one that should be considered unmissable for those reading The Artist’s Way.

NOTES:

[*] Similar to week 7’s discussion on the difference between invention and inspiration in terms of “thinking something up” versus “getting something down”.

[†]Cameron’s is laser focused on attributing artistic blocks to negative childhood conditioning from parents, which, while important, becomes tiresome and neglects other ways in which the same results may be achieved by different means. For instance, someone from a working-class background could also feel compelled to excel artistically to justify the sacrifices their made to provide their child with the opportunity to be an artist.

[‡] We should, too, mourn them as was suggested in week 8.

[§] Briefly, I wished this was something we were told from the outset of the book or was emblazoned on its cover. But I also almost instantly recognized that I would’ve unlikely to accept this point so early on.

[**] I’m closer to a 12-month than 12-week plan.

I think the first translated book I consciously chose to buy, a book I knew beforehand was translated, was Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate (translated by Thomas Christensen and Carol Christensen). It was by no means the first text (either prose or poetry) I’d read in translation, of course. As a young child, I read Pippi Longstocking, likely unaware that Astrid Lindgren wrote it in Swedish.

I think the first translated book I consciously chose to buy, a book I knew beforehand was translated, was Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate (translated by Thomas Christensen and Carol Christensen). It was by no means the first text (either prose or poetry) I’d read in translation, of course. As a young child, I read Pippi Longstocking, likely unaware that Astrid Lindgren wrote it in Swedish.