At this time of year, I normally like to compile a list of notable books that I’ve read over the past year as well as create a reading list for the year ahead. However, there’s been a change in plans this year, because I have already shared my shortlist of notable books from 2018 elsewhere. As you may know, I belong to the Women Writers Network, which is a volunteer group running a Twitter account that focuses on supporting and promoting women writers. Helen Taylor (one of the founder members and author of The Backstreets of Purgatory[1]) compiled our favorite reads of 2018. Since my top six books of 2018 appear on this list (you can find the list at Helen’s web site), I thought I’d focus on some very different reading highlights from the past year before presenting my to-be-read list, which I eternally hope to complete by the year’s end regardless of how faithless I was to the previous year’s list.[2] But I digress. Let’s get back to last year’s reading adventures.

The Alternative Reading Highlights of 2018

Procrastination Stopper

Over the past few years, I’ve participated in both reading and book photo challenges (you can view my entries to the Reading Women Month book photo challenge and Bookriot’s #Riotgrams here). Although I’ve never per se “won” a challenge by completing all the categories, it’s fun to see what fellow book lovers share.[3] Generally, the highlight of my reading challenges is that they inspire me to stretch outside my reading comfort zone or discover more diverse perspectives.[4] However, this year’s Reading Women Challenge inspired me to stop procrastinating and finish the book that’s lingered the longest on my reading list. I’m pleased to announce I finally read Woman in the Nineteenth Century by Margaret Fuller. Despite it being a more challenging read, this fascinating early feminist tract makes a strong religious argument for woman’s self-sufficiency and expanded rights. Partly inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Fuller’s work in turn spurred suffragists in the United States to demand the vote.

Most Unlikely to Be Read

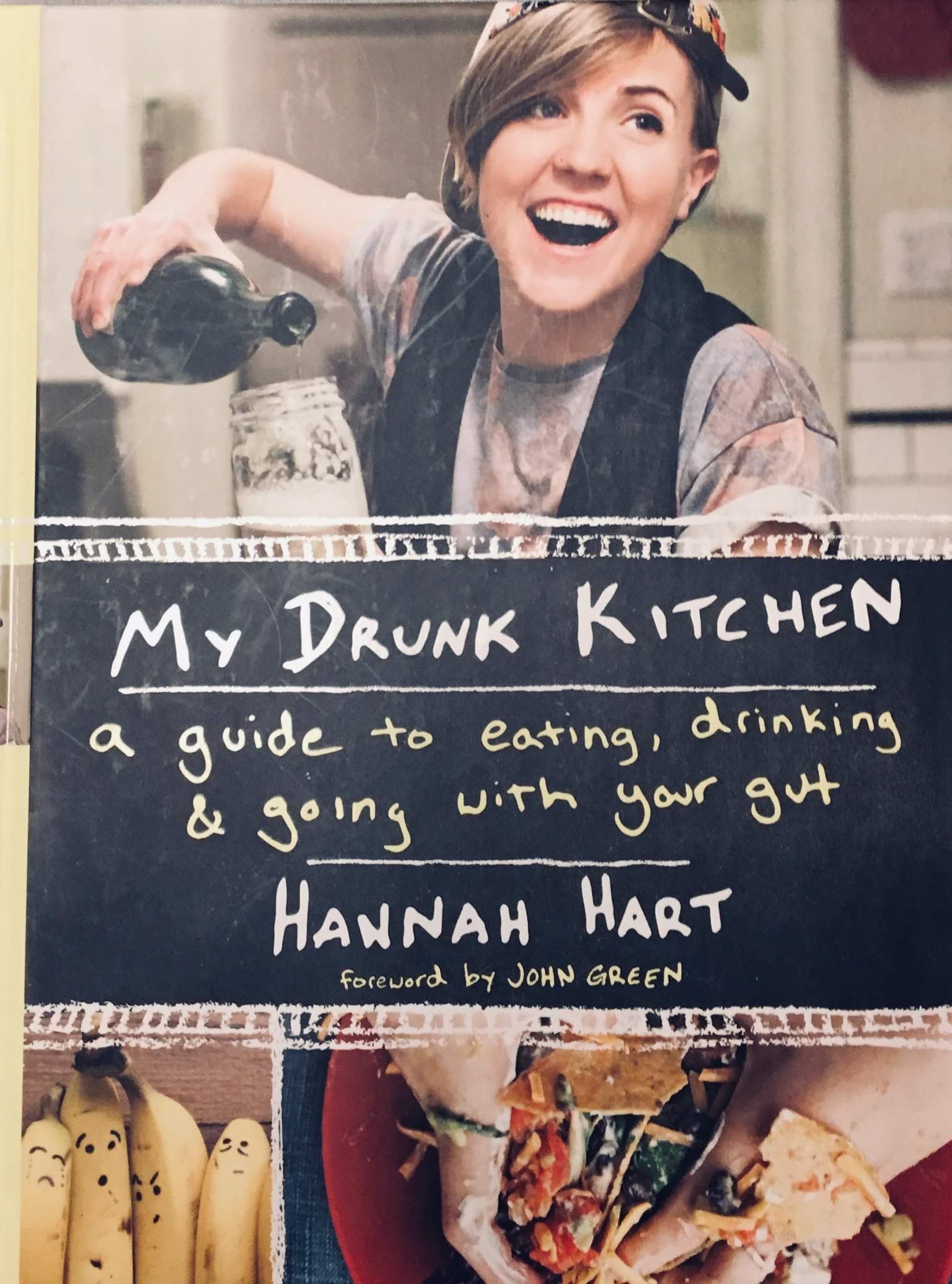

Book challenges influence my reading greatly, as do Twitter chat suggestions and personal recommendation. One of the more whimsical books I read this year is one I wouldn’t have chosen for myself, even had any of these sources suggested it.[5] Though a difficult to categorize book, Hannah Hart’s My Drunk Kitchen: a Guide to Eating, Drinking and Going with Your Gut proved to an enjoyable read. Part sentimental, part hilarious, part memoir, and part cookbook, it left me bemused but feeling upbeat. While I’m not sure I’d attempt some of the recipes, I’d definitely read it again.

Most Unexpected Source of Reading Recommendations

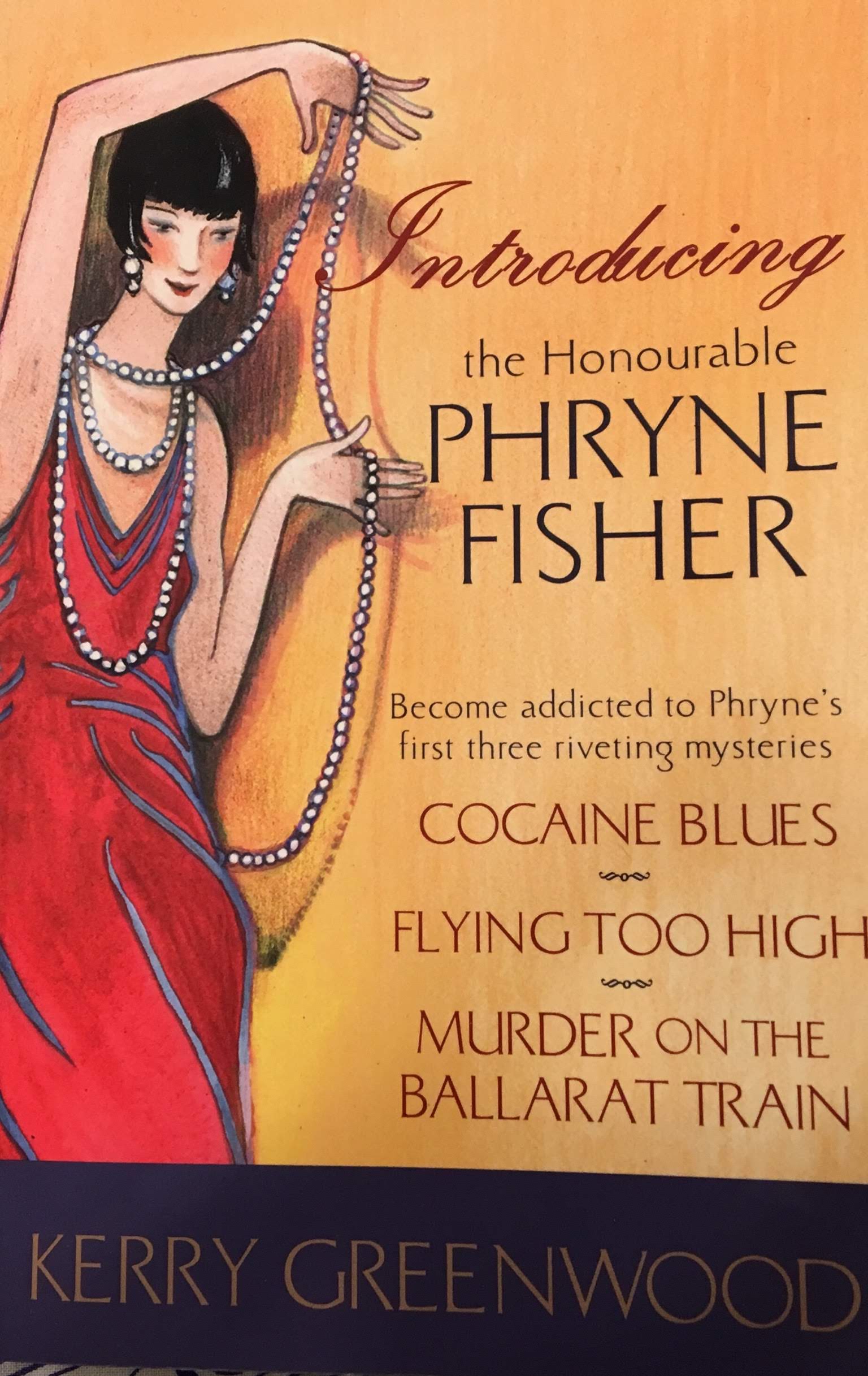

Speaking of books I wouldn’t have selected without an outside influence, I curiously have Netflix to thank for my discovering the Phryne Fisher mystery novels by Kerry Greenwood. Halfway through the first episode, I already suspected it was based on a book (Cocaine Blues), and the credits proved me right. My thoughtful spouse picked up the first three books for me, which I then read in short order. Reminiscent of Agatha Christie’s work (roughly the same period, different country, very different detective), these flapper detective novels were a great change from stuffy male detectives. Since the television series diverged a fair bit in places from their source material, I’m glad I saw it before I read it—I happen to be one of those people who usually takes a strong dislike to films/television shows when I read the book first. Either way, I intend to check out the credits in the future, in case they point me to a good book or two.

Hopefully, you’ve found some reading inspiration here, regardless of the source. Here’s to the new year and happy reading!

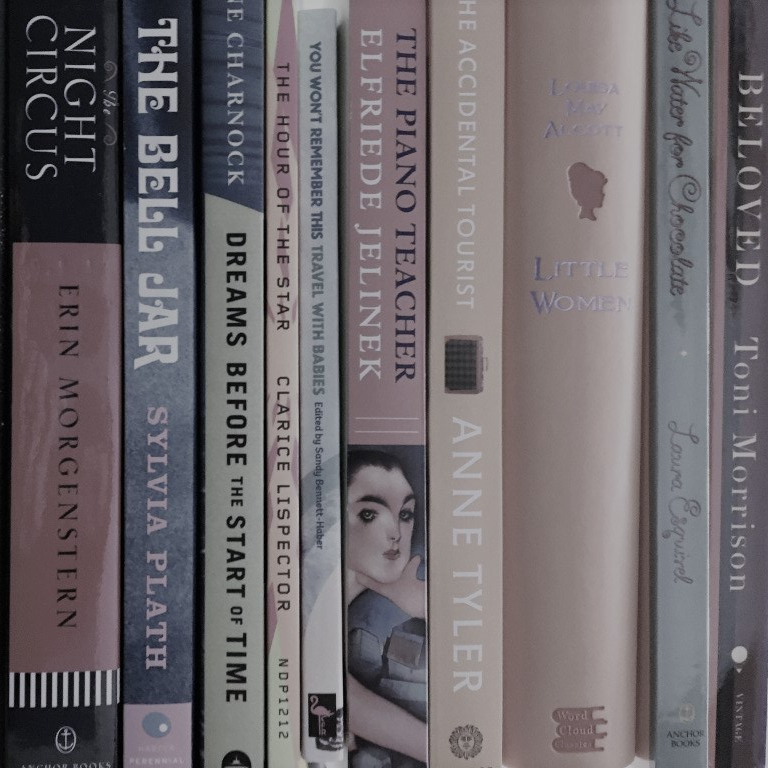

| 2019’s Reading List |

|---|

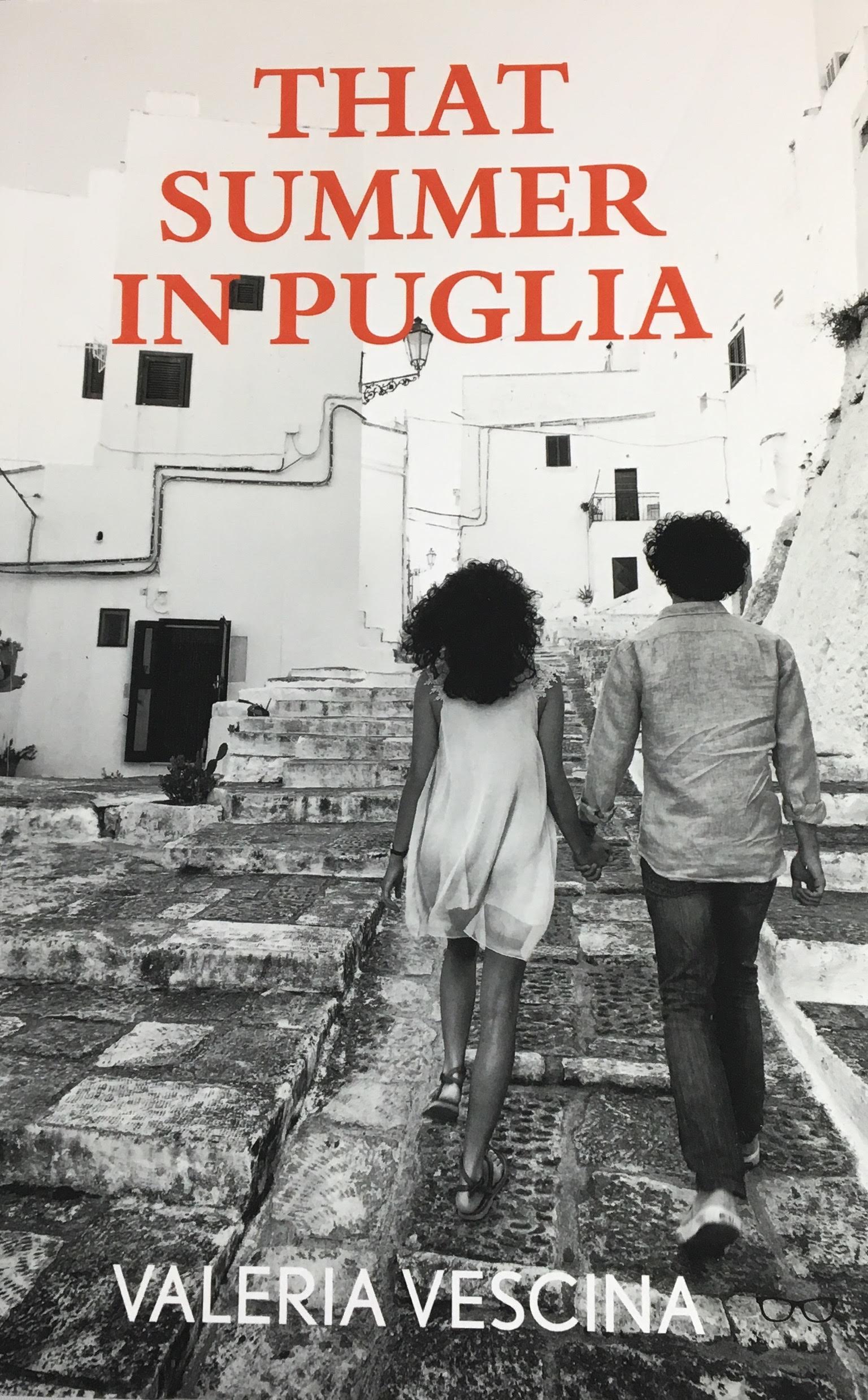

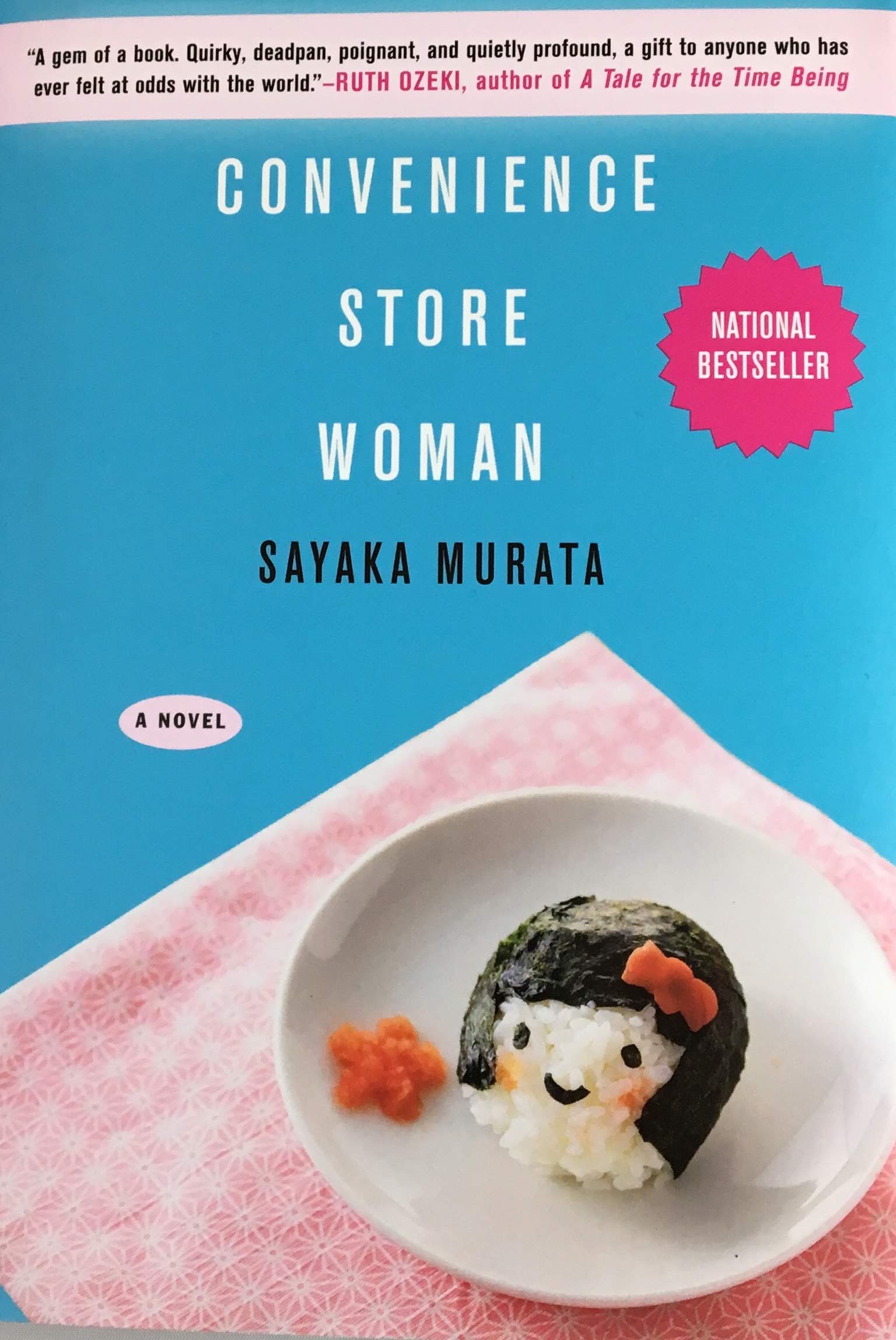

| That Summer in Puglia by Valeria Vescina Life of Pi by Yann Martel Black Faces, White Spaces by Carolyn Finney Barracoon: the Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecroft Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata (Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori) Claudine at School In: Colette: The Complete Claudine by Colette (Translated by Antonia White) Migratory Animals by Mary Helen Specht Dreams Before the Start of Time by Anne Charnock Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien The Man Who Loved Books Too Much by Allison Hoover Bartlett Take Off Your Pants! Outline Your Books for Faster, Better Writing by Libbie Hawkes Pachinko by Min Jin Lee Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman Confession of the Lioness by Mia Couto (Translated by David Brookshaw) Waymaking: an Anthology of Women’s Adventure Writing, Poetry and Art (Edited by Helen Mort, Claire Carter, Heather Dawe, and Camilla Barnard) |

NOTES

[1] My review of The Backstreets of Purgatory is

herenow available here! (Updated: 10 March 2019.)[2] Remarkably, I only missed four, one of which was a planned re-read. For the curious, these books are Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman, Confession of the Lioness by Mia Couto (Translated by David Brookshaw), Dreams Before the Start of Time by Anne Charnock, and Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. Little Women was my re-read, because I wanted to see if I still enjoyed it as an adult.

[3] In itself, a great way to get reading recommendations.

[4] These reading challenges include the Black History Month Reading Challenge (two books), Women in Translation Month (2 books during that month, 3 more later), and roughly half (around 13) of the Reading Women Challenge. I’m still working on making my reading more diverse.

[5] This book was a gift from my oldest brother who chose it because it reminded him of my food-based coffee table books (ie, The Amazing Mackerel Pudding Plan: Classic Diet Recipe Cards from the 1970s by Wendy McClure and The Gallery of Regrettable Food by James Lileks). Thanks, Jon!