I often think that the “new year, new me” vibe asks a lot of January. It feels unfair that, with a flick of the calendar, we switch from merriment to self-improvement (surely, a yearlong project) just when winter blasts into its stride. But given that change has been something of the new normal,[*] perhaps some introspection is warranted.

Certainly, this changeability influenced my reading last year. I read a respectable 45 books in 2021, mostly fiction (heavily leaning towards literary fiction and mysteries) mixed with a few memoirs. While I thoughtfully chose some books, I spent a lot of time reading on a whim. After the last few years, being flexible felt like the right approach. Many books I read also dwelled on serious and/or dark themes, perhaps another side effect of these difficult times. But what hasn’t changed is how reading connects us to ideas, places and people, both familiar and beyond our reach. Below, in no special order, are some of the books that made my reading year memorable.

Journeys: Traveling in Words

While travel stayed limited to nonexistent for many in 2021, books continued to let us explore worlds. Many of these journeys were physical, but they also could be spiritual. Although the characters in these books might be unsure of where they’re headed or if they’re ready to undertake the attendant trials, such trips often prove to be both worthwhile and, indeed, necessary.

Band on the Run

The Bellweather Rhapsody by Kate Racculia focuses on a single (somewhat wild) weekend where hundreds of high school musicians gather for an annual state festival, which happens to coincide with the anniversary of a murder-suicide that occurred in the hotel. The past is on a collision course in many ways in this ostensibly YA novel (there’s plenty for adults here), as old lovers meet, new affairs begin, a witness to the murder comes to confront her past, and a musical prodigy disappears from the room where the murder occurred. In addition to giving me serious high school music department nostalgia, it’s poignant to see these teens negotiating their encroaching adulthood while sorting out new friends and being snowbound in a creaky hotel that might have a murderer on the loose. The resolution comes with a few bangs but is satisfying in its messy, glorious finish.

Cats on the Go

Up next is The Traveling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (translated by Philip Gabriel).[†] This novel explores the bond of “pet” and their person as Nana and his human, Sakura, undertake a journey through Japan. Street cat Nana decides to live with the kindly Sakura after Sakura rescues this self-reliant feline from a serious injury. Several years later, Sakura decides that both should visit his closest friends from important times and places in his life. As Nana discovers, Sakura wants one of these dear friends to take in his cat, as a situation arises where he feels he can no longer live with Nana. Nana politely thwarts Sakura’s intentions, choosing to be at Sakura’s side through his challenges. Sakura, however, doesn’t leave his friends emptyhanded, as he continues to touch their lives and Nana learns about the events that shaped this remarkable man. While The Traveling Cat Chronicles leans sentimental in places, Sakura and Nana are a heartwarming pair dealing gracefully with life’s hardest moments.

Dreams for the Future

Rounding out this group is Madeleine F. White’s cli-fi speculative novel, Mother of Floods, which centers around the encroaching apocalypse. While the end of the world should be grim (and there’s certainly dark, difficult moments in this novel), here it proves to be an opportunity for hope. White draws on both spirituality and mythology across continents, weaving a multicultural cast of characters (the majority of whom are women) from different traditions, walks of life, and incomes. Set initially in present day with our world’s too familiar and seemingly intractable problems, Martha (England), Fatima, Badenan (both Iraq), Mercy, Chipo (both Zimbabwe), and Anjani (Indonesia) all struggle, whether it’s with a brutal marriage undertaken for survival, widowhood and debt, physical incapacitation, limited prospects, or lack of fulfilment. The common thread among them is spiritual awakening and connection. Meeting both online and off, in dreams and visions, these mostly ordinary women,[‡] with the aid of the newly ensouled Internet (a clever approach to a “ghost in machine” that gives a conscience to the information highway), these women help reshape the world into one of freedom and plenty. Unlike anything you’ve read and deeply fascinating, White’s novel envisions a better future where smalls acts lead to big change.

Glamor with a Side of Secrets

Wealth is not without its burdens and that includes secrets, both scandalous and terrible, they’d rather keep quiet. Whether it’s a character study of the woman with a façade designed to appeal to her adoring public or a high society affair turned thorny mystery, these novels let us peek behind the scenes and learn what they’re hiding.

Murder on the Island

In The Guest List by Lucy Foley, power couple Will and Jules’s spare no expense on making their society wedding a perfect, private event by choosing a seemingly charming but remote island (accessible only by boat) off Ireland’s west coast as the site for their nuptials. But, as Foley reveals, both guests and the brooding island are harboring secrets as a storm threatens. Careful to conceal the murder victim’s identity for most of the book (no spoilers here), Foley weaves in the various narrators’ impressions of events from rehearsal dinner through wedding night, revealing pasts best forgotten—and the reasons that might mark them as victim or murderer. Foley scatters numerous clues through her story, many which lead to false trails that keep readers guessing. While I did guess the victim’s identity before the reveal (after a few false starts), the killer was quite the shock. The Guest List is a well-paced, tense read that reveals guilt and hidden sins, mends families while renting others, and, arguably, serves a sort of justice.

A Star with Something to Hide

In The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, Taylor Jenkins Reid’s portrayal of a film legend is so successful you could swear that the titular character stepped out of a magazine spread, which (as it happens) is the ruse she uses to meet with relatively unknown magazine reporter, Monique Grant. Hugo, in fact, wants Monique (who she recognizes as a talented writer) to pen her biography. With both career and love life stalled, an intrigued Monique can’t refuse what may be an opportunity of a lifetime, particularly when Hugo mentions they share some mysterious connection. And Evelyn has plenty of other secrets she’s ready to air about her time in Hollywood.

As a character, Hugo intrigues on every page, because she’s an unabashedly sexual woman who remains unashamed of her desires (however discreet she must be about them; this novel involves same sex romances) and unafraid to use that sexuality as a tool to get what she wants. Evelyn’s naked ambition is a refreshing thing to see in a female character, particularly as Jenkins Reid explores the dual nature of such ambition that both helps Evelyn escape her abusive childhood and propels her to fame but also costs her identity and even love. Hollywood often put it stars through the wringer (and on the casting couch), and Evelyn is no exception. Her resilience and path back to herself and love is extraordinary. Monique, too, grows through the novel (taking more than just notes about Evelyn’s history) and finds herself inspired to demand more from her own life and prospects. As Monique becomes increasing fond of her subject, Evelyn reveals regrets, which, of course, risks this regard. A story reflecting on the price of fame, The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo manages to give us a complicated portrayal of woman living behind the glamorous mask

The Dark Side of Sisterhood

Literature has its fair share of loving sisters who persevere through hardships (eg, the March sisters from Alcott’s Little Women), some who unwaveringly support each other as they survive challenging upbringings (as Jeannette Walls recounts in her memoir, The Glass Castle).[§] However, the books I’ll be sharing do not belong to their numbers. Reminiscent of Oyinkan Braithwhite’s novel My Sister, the Serial Killer (from last year’s review), these sisters are more inclined towards mischief, malice, complicity, and some unhealthy co-dependence. Each reveals a fascinating though upsetting look at sisterly love.

The Recluses

In We Have Always Lived at the Castle by Shirley Jackson, we meet the reclusive Blackwood sisters, Constance and Merricat, six years after most of their wealthy family perished by poisoning that both avoided. Living with the now handicapped sole survivor of the poisoning, their Uncle Julian, the group ekes out a happy enough existence. Only the unusual Merricat (the book’s narrator and a clever young woman who seems rather immature for her age) ventures into the nearby village when she fetches books and supplies. The family, once quietly resented for their wealth, is now openly ostracized after Constance’s acquittal for their family’s murder, with Merricat often being tormented by the angry villagers.

Merricat, who lists sister Constance among her favorites despite her being the likely murderer,[**] is dismayed when her sister suddenly shows signs of wanting to rejoin society at the behest of loyal family friends. To make matters worse, their cousin Charles drops in for a visit. Merricat resents Charles’s intrusion, as he clearly wants to curb her wildness and expresses far too much interest in the family money. Without giving more away, the ending is both dramatic and near perilous for the sisters who nonetheless choose each other and their solitude, right or wrong, as Charles leaves emptyhanded, and the villagers end up repenting their misdeeds.

An Inseparable Pair

Sisters, by Daisy Johnson, is a dark, disturbing look at sisterhood. Fleeing from Oxford after some harrowing school incident involving sisters July (the primary narrator) and September, the girls and their mother, Sheela (the secondary narrator), arrive at Settle House in North Yorkshire. Located by both the moors and the sea, the aptly named Settle House adds a gothic element, as the dilapidated structure provides little respite as it reluctantly shelters the troubled family. The girls, born 10 months apart, share a suffocating, with elder sister September ruling the pair.

Throughout the novel, Johnson slowly parses out the puzzle pieces that reveal why the family left home so abruptly. Their backstory involves both violence and abandonment. September and July respectively resemble parents Peter and Sheela, both in looks and character. Peter proves to be a controlling man who was violent with both his own sister (Settle House’s owner) and wife, and who left the family long before he died. The more fragile Sheela is a single, working parent who suffers from crushing depression—a combination that often forces the children to shift for themselves (Sheela, in the throes of depression, rarely leaves her room during the novel). Johnson’s pacing allows the tension to increase in pitch, with each revelation hinting that the truth to come is worse yet. However, the revelations by no means spoil the shocking twist, as July’s devastating choices prove the ties that bind are inescapable in this novel.

Reading Resolutions

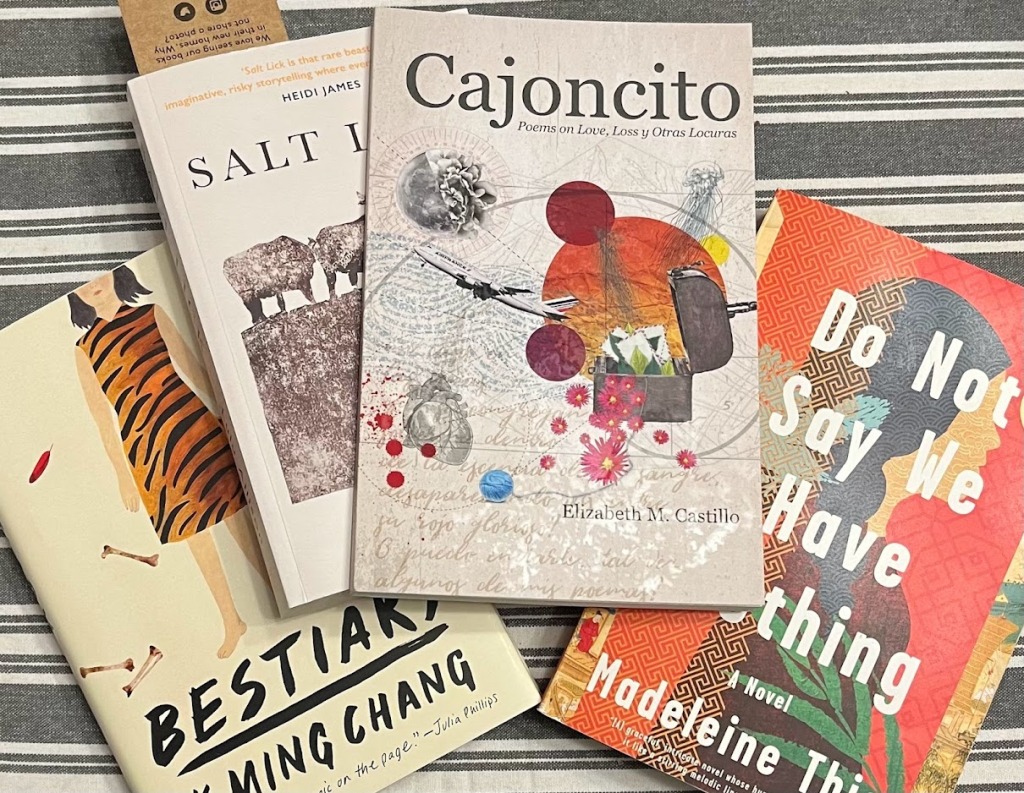

While I may not be a huge fan of January resolutions for myself, I mind them less for my yearlong reading goals. I am continuing to work on both my writing projects and my writing process, which is an ongoing process. Since November/December, I’ve been working through The Artist’s Way (first sampling the text, and now, in January, going through the lessons) to see what insights I might glean. I’ve also put together a few books that I’d like to read by the year’s end in addition to the six(!) books I already finished this year. While my list is shorter than it has been in the past (keeping last year’s flexibility in place), it includes books I’ve meant to read already (again), ones from indie authors, and even poetry. As always, I look forward to the year in reading and wish you many good reads as well!

| 2021 Reading List[††] |

| The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron Take Off Your Pants! Outline Your Books for Faster, Better Writing by Libbie Hawkes The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien Bestiary by K-Ming Chang The String Games by Gail Aldwin Dear Blacksmith by Beverley Ward The Salt Lick by Lulu Allison Cajoncito by Elizabeth M Castillo |

What are reading in the new year? Share in the comments below!

NOTES

[*] The resolve to stay safe but separate in 2020 turned into the hope of Spring vaccinations. But, as more variants emerged, we’re reminded we’re not quite through this storm.

[†] This book, written by a woman in translation, was recommended to me during #WITmonth. And…it’s about a cat.

[‡] Billionaire entrepreneur Anjani might have humble roots, but her life story is extraordinary in many ways.

[§] Walls’s memoir recounts the unusual, difficult upbringing her parents gave their children (including Jeanette, her sister, and brother) who worked as a team to make better lives for themselves and, when permitted, their beloved parents.

[**]Guests, unlike Merricat, are appalled when Constance offers her cooking.

[††] You can find previous years reading reviews from 2017, 2018, and 2019 by clicking the links.