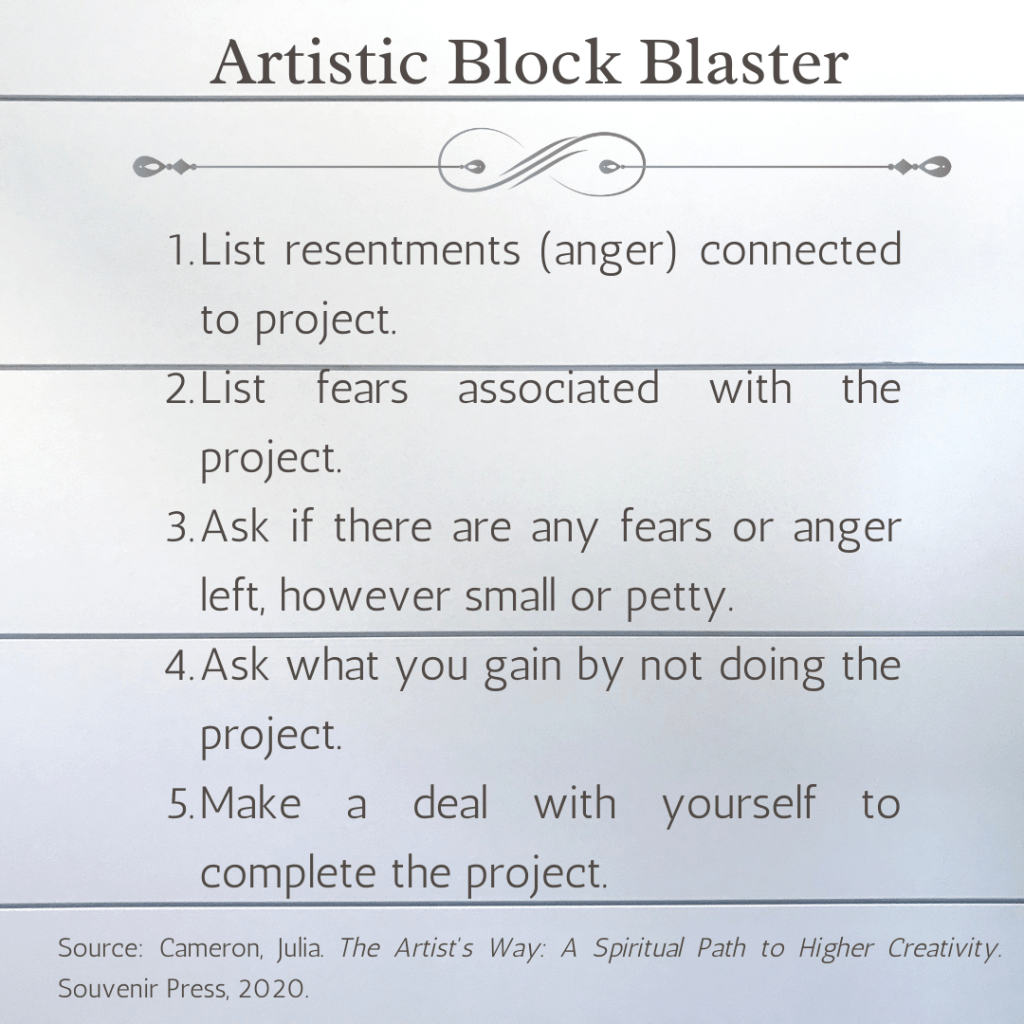

Week 9 provides the framework for blasting through our artistic blocks. Certain hazards, however, still exist for sustaining our creativity. Week 10 investigates how to protect our creativity by recognizing and neutralizing these threats.

Dangers of the Trail

Each creative person has a myriad of ways to block creativity.

Cameron starts this week on self-protection with “blocking devices” (eg, sex, drugs, food, alcohol, etc.) associated with addictions. She claims that artists with creative doubts may choose to shut down their creative flow using one or more of these blocks. Noting that these devices only become “creativity issues” when abused, she cautions us that these coping mechanisms at best assuage fears momentarily but are ineffective long term. She urges us instead to abandon this tactic. Identifying our coping mechanisms is key, as we’ll eventually take note of when we’re on the cusp of a creative U-turn before choosing to use our block(s).[*] In these instances, Cameron recommends that we employ the nervous energy generated by our artistic fears to instead create something. However, individuals who are concerned that they may have a substance use disorder or behavioral addiction (eg, gambling disorder) should seek help.

Workaholism

Workaholism is a block, not a building block.

Cameron then delves into workaholism, which was a recently identified process addiction (now behavioral addiction) when The Artist’s Way was published (1993). Cameron argues that working long hours represents avoidance, not “dedication”.[†] While she respects working toward “a cherished goal”, she remains concerned with how excessive working blocks “creative energy”. She, therefore, provides a questionnaire to assess our work–life balance so that we can assert more appropriate boundaries if needed. A small caveat should be observed here, as people may work too much for other reasons (eg, economic necessity, caregiving). While the dangers linked to overworking remain, the solutions are likely different.

Drought

For all creative beings, the morning pages are the lifeline…

Creative droughts represent long periods of being creatively blocked, which Cameron assures us occurs commonly in artists’ lives. However, lengthier stretches of being blocked can further compound our blocked state, because we tend to interpret the duration as a sign that our creativity is gone or never really existed. However desperate droughts may be, Cameron believes they serve the purpose of bringing us “clarity and charity” because we refuse to give up. To survive a creative drought, she suggests that we stalwartly continue with morning pages to work through our fears and find our way back to our creative path.

Spiritual Drugs

Fame is really a shortcut for self-approval.

When we focus on competition…we impede our own progress.

Finally, Cameron includes two “spiritual drugs” to the ways in which we spiritually block ourselves: fame and competition. Fixating on either the desire to win (competition) or for recognition (fame) can derail our creativity because both redirect our attention from creating to comparing ourselves (usually unfavorably) to others. Fame, according to Cameron, “creates a continual feeling of lack” if we’re not recognized “enough”, while being competitive [‡] makes us monitor what sells instead of seeking our own artistic inspiration. We may even abandon nascent projects should they fail to show their potential quickly. Cameron warns strongly against this impetus, noting that even “bad work” can lead to new artistic horizons.

Cameron has theories on why people pursue external validation (ego for the competitive, fears of being unloved for fame seekers), but her antidote for both is self-approval. For fame seekers, she advises us to nurture our artist to reassure ourselves of our worth and to partake in creative play (eg, artist’s dates) to forget our craving for fame. For competitive artists, she notes that self-approval supplants the desire for others’ approval, reminding us that “showing up for the work is the win that matters.”

Some Closing Thoughts

Spiritual maladies[§], as described above, are this week’s insidious creative bugbears and involve situations that may crop up during an artist’s career. Self-protection is the week’s stated goal, but building resilience is another way of thinking of it. Affirmations, morning pages, and artist’s dates are the core recommendations for issues discussed this week, all of which work towards building that resilience.

Having said that, certain discussions about addiction gave me pause. To Cameron’s credit, she remained relatively nonjudgmental and kept the conversation centered on how self-soothing with substances/behaviors harms creativity. Equally valuable was her push for honest evaluation of worrisome behaviors, which is necessary for personal change. But I found her theory on creativity and addiction puzzling[**] and her recommendation to “use anxiety” concerning. The latter reads like “use willpower”, which isn’t necessarily the best strategy for those dealing with addiction however helpful it could be for others. As I’ve stated before, this book hasn’t had a substantive update on mental health issues. Readers should refer to recent literature or the appropriate health professionals for current thinking here.

With that said, there is one standout tenet that I’d like to emphasize from this week. Cameron reminds us that we always can find our artistic direction again and again, regardless of whether we’re derailed by life or our own blocking. It’s one of the more important points of The Artist’s Way and a good reminder for all of us wherever we are on our creative journeys.

Updated on 13 August 2024 to add captions to photos and updated a term.

NOTES:

[*]Per week 9, sudden indifference towards one’s artistic projects also signals an impending creative U-turn.

[†]Workaholism may also mask underlying psychiatric disorders.

[‡]Focusing on self-improvement is key here. While competition has its uses, less competitive people tend to be more successful in the long run.

[§]Cameron considers them to be spiritual issues as these blocks specifically stop the flow of creative energy that she defines as divine.

[**] Cameron states that “it could be argued that the desire to block the fierce flow of creative energy is an underlying reason for addiction”. For what it’s worth, most evidence seems to suggest that causes of addiction are multifactorial, with genetics playing an important role.